Professor Michael Burawoy, 1947-2025

Burawoy joined the Berkeley Sociology Department as an Assistant Professor in 1976, after earning his PhD in sociology at the University of Chicago (1976) under the supervision of Professor William Julius Wilson. Burawoy’s scholarship, graduate mentorship, undergraduate teaching, and professional leadership profoundly shaped the Berkeley sociology department, the discipline, the profession, the university, and sociological practice and publics around the globe. He retired in 2023 after 47 years of service to the university, but he continued to mentor graduate students and remained very active in the discipline.

For nearly five decades, Professor Burawoy was a leading intellectual influence in the

discipline. He published 12 books and well over 120 papers, essays, and book chapters. Many of Burawoy’s published works, including Manufacturing Consent (1979), The Politics of Production (1985), and The Extended Case Method (2009), were translated into multiple languages. He is famous for his myriad generative contributions to sociological theory, sociological methods, analyses of labor processes in industrial worksites, analyses of the university as a place of work, and especially in more recent years, for his work to advance public sociology as a distinctive, legitimate mode of doing sociology in and through engagement with non-academic practitioners and collaborators, always with an orientation to the public good. His contributions to the profession have been recognized by numerous awards, including the Lifetime Achievement Award from the Marxist Section of the American Sociological Association (2020) as well as the W.E.B. DuBois Career of Distinguished Scholarship Award (2024).

Burawoy was a transformative leader on campus and in the profession. He served as Sociology Department Chair (1996-1998, 2000-2002) as well as co-Chair and Secretary of the Berkeley Faculty Association (2015-2021). He was elected President of the American Sociological Association (2003-2004) as well as President of the International Sociological Association (2010-2014). Across these various constituencies and communities, Michael Burawoy’s leadership and service was characterized by intellectual vision, political commitment to raise voices of those at “the bottom” or the margins, dedication to advance the public good, and integrity, generosity, compassion, and good humor.

As President of American Sociological Association, Burawoy developed and advanced his call for “public sociology” a call that energized more diverse and younger generations of sociologists to practice sociology through proactive engagement with concerns and questions that emanate from communities beyond academia. As President of the International Sociological Association, Burawoy made sustained and effective efforts to build infrastructure for sustained scholarly exchange among and between scholars of the “global south” and the “global north.” His contributions as ISA president made a huge impact on American sociology by increasing openness and attention to global issues and exerting counter-pressure on some of the inward focused, provincializing tendencies of the discipline in the U.S. He was founding editor of a new ISA journal called Global Dialogue (2010-2017) that featured the work and ideas of sociologists from around the world, translated into multiple languages to reduce barriers to scholarly exchange, and to remove excuses for failure by U.S. based scholars to engage with scholars from the global south.

Burawoy’s teaching and advising were legendary, as were his commitments to the continual improvement of pedagogy and to sustaining accessible, high-quality public higher education. He won numerous accolades for his teaching and mentorship at the graduate and undergraduate levels over his career, including the UC Berkeley Distinguished Teaching Award (1979), the American Sociological Association Distinguished Teaching Award (2003), and the Faculty Award for Outstanding Mentorship of GSIs (2007). His impact on students was profound. He supervised no fewer than 80 dissertations. And for four decades, he taught the department’s required undergraduate theory sequence and was renowned for learning the name of each and every undergraduate student he taught by the second week of class, even in large lectures with more than 200 students.

Upon his retirement, Professor Burawoy was awarded the Berkeley Citation (2023), one of the campus’ top honors, reserved for “distinguished individuals or organizations…whose contributions to UC Berkeley go beyond the call of duty and whose achievements exceed the standards of excellence in their fields.”

Remembrances and Tributes

Soziologie im Interesse der Humanität: Nachruf auf Michael Burawoy by Brigitte Aulenbacher

Michael Burawoy: Soziologe im Kampf für eine befreite Gesellschaft by Klaus Dörre

Michael Burawoy's Personal Website

Michael dedicated 47 years of his life to Berkeley, contributing immeasurably to the discipline, transforming the fields of labor, ethnography and theory. He was past president of the American Sociological Association and the International Sociological Association. His greatest legacy, though, went far beyond the many books and articles he published or prestigious awards he received -- it was in the people whose lives he changed. He was an extraordinary teacher, who mentored and inspired thousands of students, changing their lives with his fierce intellect and kindness.

He mentored me when I first arrived at Berkeley as an assistant professor. I learned to love Berkeley through his eyes. I learned what it meant to teach, to mentor, to do research seriously, and above all, what devotion to one’s calling looked like. I am grateful that in my present position as dean, I will always have his voice in my ear, reminding me that it is my duty to think above all about the needs of those most disadvantaged, the powerless, those who had to fight to get here.

I will miss him always as a beloved friend, mentor and comrade. An unimaginable loss.

Tribute from the Berkeley Faculty Association

The Brazilian Society of Sociology (SBS) expresses its profound condolences upon hearing news of the death of Michael Burawoy, professor in the Department of Sociology at the University of California, Berkeley and former president of the American Sociological Association (ASA) and the International Sociological Association (ISA). Throughout his career, Michael articulated like few others, the multiple dimensions of a sociologist's job as educator, researcher, and activist.

As a sociologist, Michael was renowned for the extended case method, which he developed at the School of Anthropology in Manchester, his home city. During his field research –which began in the 1960s in a copper mine in Zambia, continued in an engine company in Chicago in the 1970s, in factories and steel mills in Hungary in the 1980s and, finally, in a modular furniture factory in the former Soviet Union in the early 1990s – Michael perfected the theoretical-methodological tool that would make him known worldwide. He specialized in combining critical sociology with heterodox Marxism. In addition to classical Marxists, he drew upon thinkers such as Antonio Gramsci, Rosa Luxemburg, Leon Trotsky and Frantz Fanon in order to reconstruct the capacity for practical intervention through critical thinking, both inside and outside the university.

At the same time, he supervised his graduate students’ ethnographic projects across the globe. Among his many contributions, three stand out: the sociology of labor, sociological Marxism, and public sociology. In the case of the sociology of labor, books such as Manufacturing Consent: Changes in the Labor Process under Monopoly Capitalism and Politics of Production: Factory Regimes under Capitalism and Socialism, were critical. They led to revisions of previous analyses and generated new perspectives in the field.

Alongside his close friend, Erik Olin Wright, Michael engaged in a broad theoretical project to reconstruct “sociological Marxism” – defined as the theory of the contradictory reproduction of capitalist social relations – whose objective was to rescue the emancipatory power of Marxist theory, dismantled after the collapse of bureaucratic state socialism, starting from the critical production of empirical data. This theoretical-political program was carried forward through two major initiatives: Erik Olin Wright created the “real utopias” project, while Michael developed his proposal for a “public sociology.”

Both Michael and Erik endeavored to “reconstruct Marxism” by inviting the sociological community to be part of a broad social movement to transform capitalism through critical engagement with different audiences, academic and non-academic, that make up the world of sociology. Michael nurtured strong relationships in Brazil, visiting us among us on several occasions, whether to participate in meetings of the National Association of Graduate Studies and Research in the Social Sciences (ANPOCS), Brazilian Sociological Society (SBS) and Latin American Association of Sociology (ALAS) Congresses, or to give seminars at universities across the country. Some of his books have been translated into Portuguese, such as Marxism Meets Bourdieu (Editora da Unicamp) and Sociological Marxism (Editora Alameda).

Michael cultivated personal relationships in ways that few others do. Everyone who had the privilege and joy of knowing him, whether as a teacher, colleague, or friend, know that he was simply remarkable. The world of sociology mourns this tragic, violent, and senseless death, demanding immediate clarification from the Oakland police authorities. The large extended family he cultivated throughout his life, however, celebrates his legacy of knowledge, empathy, generosity, passion, wisdom, and solidarity.

Text by: Ruy Braga, Professor, Sociology Department, Universidade de São Paulo (USP), and Marco Aurélio Santana, Professor, Sociology Department, Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro (UFRJ); Translated by: Alice Taylor (E Korbel School of International Studies, University of Denver)

One of the things that those of us who loved Michael Burawoy loved so much about him, was that he was SO much fun and SO hysterically funny.

In 2001, we, his seven TAs for social theory, decided it would be hilarious to take the world famous Marxist sociologist to the mecca of capitalism for spring break—Las Vegas. He was game for anything, and he PAID for everything we ate there too! I think we took him to the cleaners after one meal at the Paris.

He was a good sport when we insisted he try the water massage machine—we even prepaid for it so he could not say no. The machine tickled and so he couldn't stop giggling— which resulted in all of us ROLLING on the floor laughing so hard we could barely breathe….

Eréndira dared him to wear red leather pants to the sociology department holiday party. He said, "Where am I going to get red leather pants?" (he was trying to get out of it). So Eren said, "I'll take you shopping for them." She took him to a thrift store and found these for him and he kept his end of the bargain. He looked too cute!

Everyone who worked with Michael adored him. He brought out the best in all of us, and he cared SO MUCH for all of his students.

He and I had a running joke because he thought I hugged too much. He'd say "Don't come near me with your hugs, Tamara!" Then when I graduated from Berkeley...He gave me one of the biggest, warmest hugs of my life, laughing the entire time.

Eréndira Rueda took this beautiful photo of Michael with his great friend Erik Olin Wright in 2002. Every Thursday night after our weekly TA meeting, Michael treated the seven of us to a REALLY nice dinner (wine always included). Erik joined one night at Yoshi's for dinner and music. When Erik passed away, both Eren and I separately had the same thought—had Michael saved it digitally after 18 years? He was a Luddite, without a tv, cell phone, or car, so who knew? We each sent it to him and got the same response—yes, he still had it and "This was Erik's favorite photo of us.” We knew it was his, too.

-- Tamara Kay, Berkeley PhD 2004.

A truly inspirational professor who will always be remembered. I was incredibly fortunate to have him as one of the advisors for my master’s thesis back in 1981. I still recall his insightful comments, which motivated me to work harder and produce a better paper. His classes and seminars left a lasting impression on me and continue to shape my worldview to this day. I am deeply saddened by the sudden loss of such an extraordinary teacher.

Pamela Stefanowicz, UC Berkeley - Class of 1979 (B.A.) and 1981 (M.A.)

Article For Michael Burawoy: A Tribute to a Life of Thought and Action

This is news too cruel to believe, too sudden to accept. Michael, you are gone, and yet you are everywhere. Only three weeks ago, we sat together in Cambridge, speaking of Gaza and Syria, of struggles that animated your restless mind. The day before you left us, we exchanged emails about a statement supporting BDS, a cause you carried with conviction, hoping to rally former presidents of the International Sociological Association to push the current Executive Committee toward courage. You were never just a scholar, never merely an academic voice in the wilderness. You were a guide, a force, a mentor, a friend—the kind of thinker who did not merely theorize justice but pursued it with relentless passion. I owe you so much. You took my hand and led me from the narrow corridors of professional and policy sociology into the vast, unruly terrain of public sociology. But more than that, you unmapped my thinking, urging me to embrace global sociology.

How do we imagine public sociology without your unyielding presence, without your tireless interventions? Your wisdom was never distant, never encased in ivory towers—it was lived, argued, practiced. You wrote a beautiful preface for my forthcoming book, Against Symbolic Liberalism: A Plea for Dialogical Sociology. When you saw my cautiously optimistic position on Syria, you wanted to add a paragraph on how I put my dialogical sociology into practice. You believed, always, that theory must breathe, that it must find its way into the fabric of lived experience.

In Cambridge, I urged you to write your autobiography, and you promised me you would. But fate has stolen you too soon. We are left with the work you have done, but not the work you still had to do. The world still needs your boundless energy, your unwavering commitment to justice, your fearless questioning of power.

Michael, you were not just a theorist. You reshaped the very practice of sociology, making it urgent, engaged, and alive. Your ideas do not die. Your presence does not fade. You are not gone; you are inscribed in every struggle for truth, every act of intellectual courage, every fight against injustice.

I grieve this immense loss. But I do not say goodbye.

Your memory is eternal.

By Sari Hanafi

Former president of the International Sociological Association.

Currently a professor of sociology at the American University of Beirut and chair of the Islamic Studies program. He is the editor of Idafat: the Arab Journal of Sociology.

Photo in Yakohama Congress 2014

My letter to Michael Burawoy – Marcel Paret

February 5, 2025

Dear Michael,

I learned yesterday about your passing, which happened the night before. The news reported that you flew 75 feet into the air. Wow. I suppose I should not be surprised. You were always reaching and grasping for new heights. Always leading the way, even as you were always learning and eager to learn. You certainly are fearless. Or at least very good at hiding your fears. I am picturing you soaring up and away from Grand Avenue, throwing a peace sign as you head towards somewhere else. If I allow myself to keep drifting into this dream, I see you headed to a place where you can meet other sociologists of the past – your old friends, and also those who you spent a lifetime talking to but never met in person. I dream that Marx and Gramsci and Polanyi and Fanon are waiting for you with a cup of tea.

But you have left us behind and now we are grieving and wrestling with your absence. Zach wrote to you online: “now that you’re gone, it feels like there’s a gaping hole.” And that captures a lot for me. In the acknowledgments of my book, I wrote that I took comfort in knowing that I could always count on you. It was grounding to know that you were out there in the world, always ready for a chat if need be; and in the meantime, you were always pushing for a vibrant and just and politically engaged sociology – providing inspiration and a model for us to follow. And now you are gone, forcing us to figure out what it means to forge ahead without you.

Losing you is extremely hard. You had so much still left to do and we had so many more conversations to have. I was looking forward to seeing you on the call next week about organizing for Palestine, and then at ISA in Morocco. Just a few days ago we were going back and forth about your foreword to a republication of Eddie’s book, and Zach and I got to share our recent paper on Communist parties in the US and SA. We are in the middle of writing a piece about your early work on race and class, exposing its limits so as to build a theory for the present. I was working on it just minutes before I got the news. I thought that we would have a chance to discuss and debate after the piece was done and published, alongside dialogues about Du Bois, Fanon, and Hall. We, the community that loves you, may never have been ready for you to leave us. And so, this was always going to be hard. I certainly was not ready.

You have touched the lives of so many, and I feel lucky to have been part of your life and your glow. One of my Utah colleagues wrote to me today. She only met you once, briefly. But she told me that you “left a lasting impression--his energy was contagious. It was clear how deeply admired and respected he was by everyone who knew him.” Your energy! How did you manage to stay so alive and so present for everybody? How did you make each person feel so special, while at the same time being so stubborn and committed and outward with your beliefs and your devotion to social justice? I think it was your appreciation for humanity, and the humbleness that came along with that. What a gift you were to the world, to sociology, and especially, to those of us who got to connect with you in person. I know that your legacy and your humanity will continue to ripple for many, many years to come. But right now, I am just appreciative for what you have done, and I am crushed by what we no longer get to enjoy.

Eric Klinenberg posted this: “I don’t think anyone has ever loved sociology more than Michael Burawoy. I know that no one has ever loved their students more, or done so much to bring them together into the kind of community every scholar wants. What a beautiful life. What a devastating loss.” I just had a text exchange with Laleh. All we could do was send heart emojis to each other, some whole and some broken. Back when we were writing dissertations, and going to Occupy everyday with Emily, somehow you managed to support us academically, politically, and personally, all at the same time. And you helped to bring the three of us together. Looking back, I can see how you were a rock of our community. I am gratified that we got to celebrate you at your retirement, and that both you and the rest of us – in the hundreds – could witness and appreciate the community that you have done so much to foster among those you mentored. Cinzia put it beautifully: “I have always felt that the biggest gift Michael gave to his students was each other.”

More than 80 dissertations, as chair. And many, many more that you mentored in other roles, formally or informally. As I spoke about in my remarks at your retirement party, I could feel the reach of your mentorship and community in South Africa, where so many students and scholars benefitted from crossing paths with you in different ways. Indeed, the Burawoy family extends far and wide. I remember when I told Gay that my book title (Fractured Militancy) was a play on hers (Manufacturing Militance), she responded that her title was meant to honor and tease you, in reference to your own masterpiece, Manufacturing Consent. “I guess it’s all in the family,” she wrote to me.

Last night I sought comfort by telling my kids about you. And then Jessie and I stayed up late talking about you and all that you have meant to us – I reminded her that you would always ask about her, and we talked about how amazing you were at our wedding, charming everybody as you conducted an ethnography of my family and friends. Jessie and I got together at the beginning of my dissertation work, and so we have grown up together with you in our lives. Last year, when I asked Jessie what I should say at your retirement gathering, she remarked: “I’ve never seen you hold anybody else in such high regard.”

Now that I have gotten this far in the letter, I am finally beginning to accept that we, and I, will have to come to terms with your physical absence. We will have to begin anew, making due with what you have left behind. And that is a lot. I am reminded of the random people I have encountered here in Salt Lake City that you have touched: a former undergraduate student in your famous social theory course, who has cerebral palsy and now leads efforts in Utah to secure legal rights for disabled residents. He remembers your course vividly and fondly. Another, a good friend and psychologist, who told me how profoundly your writing on the extended case method influenced and inspired her. And another, a former graduate student who I am still in touch with, who is now using Gramsci and Hall as guidance in his anarchist organizing – when you passed, he wrote to tell me how much he had benefitted from your notes on Gramsci, which I had shared with him.

Your intellectual legacy is enormous and it will live on, well beyond my years. There seems to be little doubt about that. As you know, some of us have been working to elaborate and extend some of your theoretical contributions, contributing to the study of, as you put it in your own words, “capitalism on earth.” I sincerely hope that, once we manage to pull ourselves together, we can continue this effort.

But for those who knew you better as a scholar than as a mentor, I hope that the outpouring of support will reveal that you were much more than one of the greatest Marxist sociologists to ever walk the planet. As much as I hope to leave an intellectual mark within sociology, and to publish articles that people will read, even more importantly I hope to carry on your legacy as a great mentor and a great human. Fareen wrote, “I wish we had street funeral processions in this country, because that’s what it should be.” You are an inspiration, Michael.

One of my favorite memories with you was during my preparation for the qualifying exam at Berkeley, when I was writing an essay comparing Gramsci and Fraser, under your guidance. We lived near each other, and we would sometimes ride our bikes home together, talking about theory all the way from Berkeley to Oakland. You loved to bike, you loved theory, you loved Gramsci, and it seemed, you loved sharing your wisdom with me and sharing that time with me. I will be forever grateful. And I will cherish these memories.

So many tributes to you are coming out, from all over the world. A testament to your wide reach; and to your hunger for transcending boundaries and making connections with humans well beyond the confines of the US and the West. Among the many posts and messages, I like how some people have ended their tributes by writing, “Michael Burawoy, forever.” It gives me a tiny bit of comfort, in this moment of grief, to remember that you will live on forever in our writing, our communities, and our hearts. Keep flying, Michael.

With love, Marcel

Dear colleagues, this is to contribute to the homage we, and the sociology community world wide, owe to Michael.

I have known Michael for 40 years. He was a friend, a colleague, and a companion of many struggles for social justice. He was, and will remain, a towering figure of sociology. As an incredibly innovative empirical researcher, as a significant theorist of the centrality of labor in understanding society, and as the scholar who put public sociology on the intellectual agenda. We will miss him deeply. I encourage the young sociologists to study his work and learn about his life, about his work in/on South African mines, Chicago factories, or construction sites in Northern Russia. He should be an inspiration for 21st century sociologists. It is only fitting that such an intellectual giant would be recklessly killed by the violent society he denounced and that he tried to pacify. We will continue his work and persevere in his values.

Manuel Castells, Emeritus Professor of City Planning and Sociology, UC Berkeley

Manuel Castells, FBA.

I am disappointed and saddened to hear about the death of my former sociology professor, Michael Burawoy. Prof. Burawoy was a giant in the sociology world and was well loved and respected. I was a student of his during the pandemic, so I didn’t have the pleasure of meeting with him in person each week. However, he still made quite an impact over Zoom. He loved to hear my reading voice and would ask me to read during EVERY class (which my classmates loved because it meant they didn’t have to do it). He was a sweet and affable guy and he will be missed by so many.

RIP Professor Burawoy. Thank you for helping me to see the value in my voice.

- Carmen Drake, Class of 2021

Summary of Dr. Michael Burawoy’s Lecture on the Future of Public Education (February 23, 2017, University of Montana) Dr. Michael Burawoy delivered a thought-provoking lecture on the crisis of public universities in the United States, particularly focusing on the impact of marketization and privatization on higher education. Drawing from his extensive background in sociology, he outlined the structural transformations that have reshaped universities, emphasizing the growing disconnect between faculty, administration, and students.

Key Themes: 1. The Marketization of Higher Education • Universities are increasingly being treated as business enterprises rather than public institutions. • Public funding for universities has declined, forcing them to rely on tuition increases, private donations, and corporate partnerships. • Knowledge itself is becoming a commodity, limiting accessibility to education.

2. Administrative Expansion and Faculty Disempowerment • A five-fold increase in senior administrators at universities like UC Berkeley has shifted priorities away from education and research toward revenue generation. • Faculty are becoming more marginalized in decision-making, while adjunct and contingent faculty bear an increasing teaching load with lower job security.

3. The Role of Students in a Changing University Model • Students are paying more for less, with rising tuition and fewer resources available to them. • The shift toward out-of-state and international students as revenue sources has created political and ethical dilemmas. • Many students leave universities with significant debt and uncertain job prospects.

4. Four Crises Facing Public Universities • Budgetary Crisis: Reduced state funding, leading to higher tuition and reliance on private donations. • Governance Crisis: Administrators prioritize financial survival over academic values. • Identity Crisis: Faculty and students struggle to define the purpose of the university in a corporatized environment. • Legitimation Crisis: The public’s trust in universities is eroding as education becomes more expensive and less accessible.

5. The Need for Public Engagement and Collective Action • Universities should be accountable to the public, not just to administrators or corporate interests. • Faculty and students must reclaim control over university governance to ensure that education remains a public good. • Strengthening cross-disciplinary and community engagement is essential to resisting further privatization. Conclusion: Dr. Burawoy argued that the future of public universities depends on critical engagement, activism, and rethinking higher education’s purpose. He encouraged students, faculty, and administrators to work together to challenge the neoliberal model and push for a more democratic and accessible university system.

By SteVen Ray

I worked with Michael these past 15yrs as a staff member.

It's pretty obvious the impact he had in the academic world

but bringing him closer to home the impact he had on making

our work place a civil and sane one was important too. It was clear

to me that he really cared deeply about people no matter what

roles we're in. He respected us as colleagues with a contribution

to make.

I will be continually amazed at the memory he had. On one visit to my

office he saw a picture of my cat. He then went away on sabbatical

for a year. Upon his return I saw him in the hallway and he asked me

how Toby was! He actually remembered his name! I then shared with him

a picture of 2 kittens we added to the family (they look nothing alike) and

he said "Awww, they're twins!" Next day he brought them each a fishing pole

and some little felt mice.

He asked about my daughter every single time. The week before he passed

I told him that she was taking her first Sociology course and he immediately

replied to tell me that if she ever needed a tutor or simply someone to

explain anything to her as she moved along in the class to give him a call.

I have a weird pass time of watching UK politics. Every time something

cooky came up I always asked Michael if he'd be willing to explain

what just happened. He always graciously and patiently explained things

as he saw them. The last few times (if he was on campus) and something

in the UK was a blaze, he made his way down to my office to explain

things before I even asked him!

All this to say, I knew how busy he was with his academic colleagues, his

hundreds of undergrads, his many grad advisees, BUT he always took the

time with staff as well. I swear, he pulled extra time out of his pocket. He was never

in a rush and gave so generously of his time to us.

I will always be grateful to Michael for being part of the reason why Berkeley Sociology

is a great place to work but more importantly allowing us to make our contributions

to something big and important as we assist our "bloody brilliant" students and academic

colleagues.

Oh and "Bob is your uncle!" :-)

Rebecca Chavez

UCB Sociology

In Memory of Michael Burawoy: A Brilliant Mind, A Fierce Advocate, A Dear Friend

Hello dear community. Let me begin by apologizing for joining late. I was

moderating a session in Haifa, Israel, for a book release about Gaza.I deeply

wished to be with you from the very beginning, to share our pain together and to

not be alone in our mourning. But as I made my way here, I could almost hear

Michael’s voice reminding me: “Areej, your work and commitment to with your

community and your people is important—especially now.”

Since October 7th, Palestinians in Israel have had their voices increasingly silenced.

Michael understood the weight of these moments and the urgency of engagement.

Even after his passing, his voice still resonates with me, guiding me—urging me to

think, to write, to act, to ask what must be done. His presence, his insights, and his

unwavering commitment continue to shape the way I navigate these difficult times.

It is incredibly difficult to put into words the magnitude of loss I feel with Michael

Burawoy’s passing. He was not only a towering figure in sociology but also a daily

source of support, wisdom, and solidarity. Over the past two years, our

conversations—sometimes brief check-ins, other times long and winding

discussions. His generosity was boundless, his intellect razor-sharp, and his

commitment to justice unwavering.

As a young sociologist, encountering his work on public sociology provided me

with the tools to envision what an engaged and committed sociology could truly

be. But what made his scholarship transformative was not just his theorization—it

was how he lived it. He did not see theory as detached from practice; rather, he

embodied the belief that those who theorize must also carry the practice. His

unwavering commitment to public sociology was not merely intellectual but deeply

lived, shaping both the field and the possibilities of sociological engagement.

Michael was politically engaged in the world he studied, something that not all

scholars can say about themselves.

I will never forget his characteristic modesty or the conversations we

shared—exchanges that profoundly shaped how I think about scholarship,

activism, and responsibility. Meeting him, after years of learning from his work,

reinforced how theory gains its deepest meaning when it is carried into action. His

solidarity with Palestine was not a passing stance but a deeply rooted commitment,

one that started to permeate his scholarship and his presence—especially since

October 7th. His work and his life continue to shape who I am today, reminding me that the power of sociology lies in its ability not just to interpret the world but to engage with it and shape it.

It feels deeply symbolic that Michael’s last published article was “Why and How

Should Sociologists Speak Out on Palestine?” - a testament to his lifelong

dedication to justice. It stands as a testament to his relentless pursuit of justice.

That was Michael—never retreating from difficult conversations, always pushing us

to confront uncomfortable truths, and forever standing on the side of the

oppressed and the colonized.

Michael was not just a scholar; he was a builder of relationships, a weaver of

community. He brought us together, creating a family bound by justice, care, and a

shared commitment to a decolonized world and decolonized sociology and lastly a

decolonized Palestine. With him we shine together—our voices stronger, our

resolve deeper, our sense of belonging to one another more profound. He

nurtured a space where we could challenge, support, and grow with one another,

where intellectual rigor and political commitment were inseparable from love and

solidarity. The family he built among us is his legacy, and we will carry it forward.

When we became close, I remember the exact moment he looked at me and said "I'm Jewish Areej. I hope you won't hate me." His words caught me off guard, but I immediately felt tears in my eyes. "I will love you more, Michael," I told him. "It is a testimony for me that, as a Jew, you continue the struggle for justice." I knew

what it meant for him to do so and how deeply he believed in a true decolonial

present and future. His family “left” Germany “one minute” before the Holocaust,

he would tell me. His world and opportunities were shaped by that devastating

history of the genocide of European Jewry. I think this history, even if tacitly and

not explicitly, undergirded Michael’s dedication to liberation and justice for all, and

his view that academics cannot insulate themselves from the world around them.

Michael, I know how important it was for you that public sociologists speak up for

Palestine, especially in the middle of Genocide. This is your contribution to us—to

continue the struggle for justice, to advance the anti-colonial fight for the world

and for Palestine, and to insist on a future where we all, Palestinians and Jewish

Israelis alike, can live in dignity and freedom in a decolonized world. Michael

wrote in his last article, “For a sociologist it is not enough to declare whose

side you are on and then move on; as sociologists we embed our political

commitments within a theoretical framework. In a period of

“postcoloniality” the systematic and transparent repression of Palestinians

by the Israeli state makes it unique, compelling us to re-examine our own past, giving new salience to “settler colonialism,” as the debris of decaying Empires.”

Just two days before he was killed, I wrote to Michael, asking when we would speak

again. His response: "Always free for you! Any day, anytime. What do you make of

what’s going on in the world?" That was Michael—always ready to listen, to

discuss, to debate, to challenge and to support. And now, the world and my world

feels profoundly emptier without him. Our department at Berkeley, the field of

sociology, and the world writ large will have to grapple with this profound loss. It

still feels inconvincible and impossible that Michael has left us. It will be our work,

then, to keep Michael’s legacy alive, to share stories and teach his work and, most

importantly, to model ourselves after his beautiful character.

Michael, I will miss you more than words can express. But I promise you, we will

carry forward the struggle, and we will keep your spirit alive in the fight for justice.

Rest in power, my dear friend and teacher

Areej Sabbagh Khoury

I took Michael's undergraduate class in 1987-1988. I don't remember all that much about my time as a sociology major but I keenly remember that class. It may sound like a cliche but it really influenced my whole life since then. The class was organized around the division of labor and I've always fought against the system's push for me to focus on just one area. I remain an anti-capitalist not only based on that class, but in part.

When I arrived at UCB, I was a liberal Democrat. Through that class and other experiences, my thinking evolved to seeing the system as a class system vs. through liberal eyes. I think of myself as a small m Marxist. I continue on as a radical activist, my ongoing project being Slingshot Collective which I joined in 1988 and have worked on since then. This also informs my legal practice (day job) where I practice non-profit corporate law for clients helping the marginalized and disadvantaged.

Michael was an inspiring professor and thinker. Thanks to him and to UCB and the sociology dept.

Jesse D. Palmer

Dear Berkeley colleagues,

My deepest sympathy on Michael's passing from his alma mater. For me, a former factory worker myself, his writings were enormously enlightening. And I had occasion to consult with him several times about faculty governance and other issues here at U of C. We will miss him very much.

Sadly,

Bob Kendrick

Michael was the best teacher I ever had, and at Berkeley I had some amazingly good teachers. He taught me to be bold and political in my arguments, base my knowledge on primary sources, and apply my research and learning for social justice. I was not supervised by Michael, but he always gave me encouragement. As a footballer, I enthusiastically joined what was a short-lived departmental football team organized by Michael. I am sad to hear about what happened to him, but he will live on as a huge reservoir of inspiration for the rest of my life.

Colin Samson, PhD 1990

Department of Sociology

University of Essex

RIP to one of the greats. Michael Burawoy. You changed my time at UC Berkeley. After transferring there, I was struck by how it seemed that professors there cared far less about students than the professors in community college had. It seemed as if showing up to teach class was an inconvenience for some of them, and I’m sure it was if research was their sole desire.

Not for Burawoy, as we affectionately called him. I had him three semesters in a row and was lucky enough to be a part of his twenty person seminar my final semester. He showed up every day full of a zest and passion that was contagious. Not only did he break down complex theories into digestible pieces but he made us laugh during every lecture. Imagine a lecture hall full of four hundred students laughing together as an eccentric man with a thick British accent described the nuances of Marxism. I honestly didn’t think any part of me would love learning about sociological theory but every part of me did by the end of my time with Burawoy.

The world of academia and sociology and social justice will dearly, dearly miss you. Your presence alone made Berkeley worth coming to for each and every one of us. I think about the ripple effect of your passion for critical thinking, for truly understanding sociological theory, and how that now lives on in each of us. How important such thinking is in these times ahead. How important it is to examine the cost of capitalism especially, something you drilled into us. I hope to take from your death the reminder that we each have the responsibility to show up with zest and passion somewhere in our life. To show up with grit, to show up with fight.

Thanks for changing my life (and thousands of others).

-Adrienne Lee, UC Berkeley Class of 2016, BA in Sociology

Feb 8, 2025

Mara Loveman

I had the extraordinary good fortune to be Michael’s colleague and friend in his home department of Sociology at UC Berkeley.

Like so many others, my whole being is still struggling to absorb the reality that we are now in the world that we are in, without Michael Burawoy here with us. Waking up, things look bleak; and the Grief is just enormous, and it weighs, heavily.

In this context of shared grieving and commemorating, today, still only a few days after his death, I find that the part of michael’s contribution to sociology and to the world that I am most compelled to speak about, is his teaching.

Michael loved teaching with all of his heart. And he taught with all of his might.

He often said teaching was a privilege. He engaged in teaching as a responsibility, or even an existential mission.

Teaching was integral to who Michael was as a scholar, a writer, a speaker, an activist, a human being. I think teaching is what made Michael the sociologist he was. I also think Michael’s sociology deeply shaped the kind of teacher he was.

Michael never let us forget that Teaching is at once a social relation between human beings, and a labor relation, between worker and employer, especially in the context of the neoliberal university. Michael worked and played with this tension in different ways at different moments. Whenever there was a labor action here, he refused the Question: “do I cancel class or do I cross the picket line?” Michael never cancelled class. He taught his classes on the picket line.

I think the way Michael engaged with students embodied his determination to defend the classroom as a space where human relationships can prevail. One small example of this, which is well known here but maybe not so well known in the wider sociology world: For decades, Michael taught our required undergraduate theory courses. These took place in lecture halls will 200 students per class. (Berkeley is a huge university and undergraduate students too often learn to expect anonymity as a default). By the end of the second week of class, Michael could call on every last student in the lecture hall by name.

Michael’s teaching made individual students feel seen and valued as individuals, who had something unique and important to contribute to building a better world. He also created conditions for them to build genuine intellectual and human communities. His PhD students will tell you all sorts of ways that he did this. He did this for his colleagues and for staff members in the department too, making each of us feel special, and fostering our community through a sense of shared purpose in the radical pedagogical mission of Berkeley as a public university in the state of California.

Another small example: For many, many years, Michael gave the closing speech at our department’s graduation ceremony. Sociology at Berkeley graduates a few hundred students per year, and sometimes as many as 50% of these students are first in their families to graduate from university.

Michael would pause at one point in his remarks and ask all the students who were the first from their families to graduate from university to stand up. Then he would ask them to turn around and face their families and friends in the packed auditorium. From the perspective of us faculty members sitting in a row up on the stage, in our ridiculous robes, we got to see the faces of the parents and grandparents and friends of the standing graduates beaming with pride as they looked into the faces of the new graduates.

These were the moments I felt most proud to be a professor of sociology, a teacher, a part of the collective political project to defend and sustain the public university as a space and set of relations and conditions where it is still possible to nurture the cultivation of good sense, to help sow seeds for a more socially just world. Michael was a fierce defender of the public university and its potential to create conditions for more radical social change.

One final thing I want to share about Michael’s approach to teaching that I loved was that he was always so open, so curious, so eager to learn from others, and so game. I mean, you’d run an idea by him on a whim and he’d be like “OKEE-DOKEE!! Let’s give it a try!” One time, when I was Dept Chair, the idea was to take the first year cohort of graduate students for a little hike. A chance to get to know them, at least a little bit, as human beings, and for them to start to get to know each other, before the Fall semester consumed them. Next thing I know, I’m renting a van with 14 seats, picking up Michael who is ready to go in his black adidas track-suit, and heading north across the Richmond bridge to his favorite trailhead in Pt Reyes. We carried with us a van-full of unsuspecting students who were about to be embarked on a 15km out and back trek to the edge of a cliff overlooking the pacific ocean. I’m pretty sure several of those students swore off hiking forever after that. But it was a good day. We fed them ice cream on the way home.

And that happiest of memories – hiking with Michael Burawoy and a gaggle of new sociology graduate students on his favorite trail in Pt Reyes - brings me back to my grief. That enormous, heavy grief I named just a few minutes ago.

My colleague and friend Dylan Riley reminded me earlier this week that grief weighs on us because grief is not only sorrow for what is lost. Grief weighs, because it is responsibility, for what remains.

Here at Berkeley, we feel a responsibility to carry forward Michael Burawoy’s work, on so many fronts. He left way too soon and there is so much work that is unfinished.

As I think about gearing up to rejoin the struggle, I’m inspired by Michael’s teaching as a pillar of his life’s work - starting with the way he practiced teaching as refusal of the commodification of learning, and as resistance against neoliberal and managerial pressures within the university that would diminish and deaden and devalue our genuine connections with each other and with the world.

I’m feeling like right now, those pressures are increasing, and we need to train ourselves against them. To start, we could put on our own personal equivalents of Michael’s black Adidas track suit -- and take a walk with friends. Friends we already know and trust and love, and friends we are open to getting to know - open in the way Michael always was – to new humans we might learn from, and to new and more just communities we might form and become, as students and as teachers, all of us always both.

Today, the weight still feels really heavy. But I’m hoping that with practice, I/we will learn how to carry this weight more lightly, and even with good humor, as Michael Burawoy did. As I think about the tapestry of extraordinary human beings here in Berkeley and across the globe who are knit together at this moment through our connections - and our myriad ongoing conversations – with Michael Burawoy, I think we will make a good try of it at the least.

--

The death of Professor Burawoy is a profound loss to the world.

I was a sociology graduate student from 1960-1966, followed by an academic career. I witnessed the vision, scholarship, and leadership of Professor Burawoy in the students and administrators he mentored. His spirit will continue to guide me.

J.Herman Blake

Professor Emeritus

Medical University of South Carolina

Iowa State University

Tribute to a legend, a true Sociologist. A revolutionary deep thinker and an intellectual, Professor Burawoy will be profoundly missed. His legacy lives on in the students and people he inspired and the worlds he helped me (us) reimagine. I still remember the day the fire alarm went off during our Sociological Theory class. Everyone started to evacuate. So, needless to say, I was surprised when Professor Burawoy said, “We’re having class outside!” As I reminisce, that moment solidified what I had already begun to feel— coming to Berkeley was the best decision I had ever made, and Burawoy was at the heart of that realization. As a first-generation, formerly incarcerated Chicano student, I spent much of my life believing that academia wasn’t meant for people like me; society reinforced this with its policing, imprisonment, alienation.But in Burawoy’s classroom, I discovered a space where my lived experience wasn’t something to be ashamed of or conceal—it was something to explore, critique, and connect to broader social forces.

Professor Burawoys pedagogy began to transform my view of education. His classes were intellectually rigorous; they were passionate, raw, and profound. Despite struggling with the materials my first year, I was eager to learn more and enrolled in Professor Burawoys advanced theory course, dedicated to the great W.E.B. Du Bois. I thought I knew the discipline before coming to Berkeley, only to find out that I would become a lifelong learner (and that’s ok). Through Burawoys teaching, I gained a foundation in critical theory, diving deep into the works of Fanon, Gramsci, Marx, Foucault, and many more. He made power, inequality, and social structures tangible, showing me how they weren’t just abstract ideas but real, lived experiences that shaped our world. His passion for Marxist sociology wasn’t just theoretical—it was about exposing the forces that oppress and empowering us to challenge them in our own way. For me, Burawoy’s classroom was a space of counter-hegemony—a site where I could reclaim knowledge as a tool for liberation rather than exclusion. His influence extended beyond academia; it shaped my sense of purpose, commitment to justice, and understanding of the world. Thank you for everything, Professor. I will miss you, just as I miss every one of my Homies gone by tragedy.

Marx wrote, “Philosophers have only interpreted the world in various ways; the point, however, is to change it.” Professor Burawoy, you didn’t just interpret the world—you changed it. Rest In Power, BB!

Juan Flores

B.A. Sociology 2019

MPP/MSW 2026

Photo taken by Zainab Altai

I studied at Berkeley from 2006-2010, and was very interested in learning from the University’s most famous Marxist & labor scholar when I signed up for Burawoy’s 101 series. His classes framed sociological theory as a heated and ongoing dialogue on the most important questions in life. Who has power? Who should have power? What is the role of the state in society? What is the best way to divide labor among different people? The connections that Burawoy made between the readings and current events, the lecture time he devoted to directly engaging students, and his incredible persistence in remembering our names, made us feel like he was genuinely interested in OUR thoughts about these questions and how these issues impacted us. It felt like our opinions mattered, like we were actually participating in the discussion with Hegel, Marx, Durkheim, Weber, Gramsci, Foucault and Fanon.

I loved attending Berkeley, but sometimes I feel like being accepted to the University was the peak of my achievements. I have not been career driven, or had a particularly significant “impact” in the years since I graduated. I like to joke that if I put a “UC Berkeley Alumni” plate on my beat-up 2009 Hyundai Accent, the University would contact me and pay me to take it off.

But when I think of Professor Burawoy and what his teaching and commitment to public sociology communicated, I don’t feel like his time and expertise were wasted on me, or ever had anything to do with what I might hypothetically achieve. It doesn’t matter that I am currently a non-income earning, stay-at-home mother living in a one-bedroom apartment. He believed that knowledge belongs to everyone. This is why I donated to the University (for the first time ever) to support the endowment in honor of his retirement. It’s why when I saw him walking & carrying his groceries years after I graduated, I chased him for several blocks (pushing my baby in his stroller) so that I could thank him for what he taught me. The content and method of his teaching connected me with my deepest values and faith.

Professor Burawoy made me feel part of something greater than myself. I’m so sorry that he is gone, and so grateful for his mind, spirit and life.

MaryAnn Crawford Miller

Dear colleagues,

Please find my obituary on Michael Burawoy in the Vienna-based magazine TAGEBUCH

https://tagebuch.at/2025/02/soziologie-fuer-alle-zum-tod-von-michael-burawoy/

It is really sad.

With kind regards,

Jens Kastner

---

A... kademie der bildenden Künste Wien

PD Dr. phil. habil. Jens Kastner

Ästhetik und Kunstsoziologie | Aesthetics and Art Sociology

Institut für Kunst- und Kulturwissenschaften | Institute for Art Theory and Cultural Studies

In Memory of Professor Michael Burawoy

I’ve never written a tribute before, and don’t really know how to write one. To be honest, I’ve never lost someone so important to me in the past 30 years of my life. But I feel I really need to write something about Professor Michael Burawoy. I had the privilege to study social theory with him for three semesters when I was an undergraduate student at Berkeley 10 years ago. He’s one of the kindest and most humorous people I’ve ever known. He showed me what it means to be passionate about sociology and about social justice. He encouraged me to think like a theorist at a time when I—as an international student—was unsure about whether I would be able to comprehend the dense theoretical texts by Marx, Lenin, Gramsci, and Fanon in a foreign language. He taught me the importance of engaging in theoretical dialogues, challenging methodological dogmas, and asking big questions that matter in the current social milieu.

In the first week of Soc 101 back in 2015, he arranged a special session (with his amazing GSIs) for all the international students in his class. Theory, he told us, is just like another language, and even native speakers would need to learn this language as well. Thanks to what he said in that session, I became much more confident (and comfortable) about “smoking Social Theory (ST) on the beach.” Perhaps too comfortable—I asked so many questions in his class that he had to set “quotas” for me to make sure other students have an equal opportunity to participate in the classroom discussions. Nevertheless, I learned so much from participating in his lectures and in his extra “anything goes” sessions, not just about Marxism and the Extended Case Method, but also about the praxis of “living” theory. I literally cannot think about social theory and sociology without thinking about him. And I still talk to my colleagues about how much his strict word limit (e.g., explaining Marx’s theory of history in 500 words) improved my writing skills.

In the comments for my final paper for Soc 103 (an advanced theory seminar/research practicum on “Our University”), he wrote, “Yuchen, Excellent! As always you are a devoted sociologist and here you successfully engage both the Diversity Report and Durkheim … You obviously take the sociological enterprise very seriously and understand methodology with great sophistication – the idea of sequential interviewing (which by the way is at the heart of participant observation) and of the reconstruction of theory through the discovery of anomalies as you do with the diversity report. You are also keen to integrate theory with research. This all augurs well for your future as a sociologist.” When I translated this to my mom, she was so shocked that a famous professor would use the word “sociologist” to refer to an undergraduate student. But I knew that’s how he treats his students—not as passive recipients of knowledge, but as colleagues and interlocutors who are/will be producers of sociological knowledge. Indeed, I chose to do my PhD at the University of Chicago because he told me, “You are made for Chicago.” (A professor later told me that probably meant I’m not radical enough for Berkeley, but I hope he meant I’m at least good enough for his alma mater.)

The last time we met was at the 2024 Spring Institute at UChicago. He was the keynote speaker, and I presented a conversation-analytic paper about in-depth interviewing. As we all know, he’s more of a macro-sociologist studying major historical transformations through an ethnographical lens. But I turned out to be more interested in “micro” sociology—especially in that paper, I was looking at the minutiae details of conversational turns. I knew he was critical of ethnomethodology and the interactionism of the Chicago School. Still, he encouraged me to pursue that path and to continue thinking about reflexivity. I forgot to ask him if my presentation could get me a B.B. (“Bloody Brilliant,” as he always says to his students), but I guess I really need to get that paper out and carry on his devotion to reflexive sociology—even if I’m taking a different path.

This is probably a badly written tribute, partly because I’ve never written anything in this genre before, but, more importantly, because words cannot express how much I appreciate his mentorship.

I will always miss him.

– Yuchen Yang, Class of 2017

------

Yuchen Yang, Ph.D.

Assistant Professor in Sociology

School of Social Policy and Society

College of Social Sciences

University of Birmingham

Dear Berkeley Sociology community,

I am heartbroken by the loss of our fabulous Michael Burawoy. Here is my remembrance.

In solidarity,

Jordanna Matlon

*****

Michael Burawoy is so loved. I write in the present tense because the love he gave reciprocates and multiplies. It lives. As the tributes come in, his presence is clear...Michael had just emailed, had just visited, someone was reading his article, teaching his book, or only this week speaking about him in class (as was I). Michael had the ability to be everywhere at once and when he was there, he was always and fully present. He made me and so many of us feel special. I very much hope that all of us who love him remember him by his life and not his death. We owe him that much.

Michael was pivotal for my intellectual trajectory. I had the dumb luck of having him teach my first year PhD Social Theory course. I went on to take a four-student-led Marxism reading group with him as our advisor, then a year-long independent study under him as chair of my MA thesis, and later he chaired my qualifying exams. I thought my dissertation was doing something different so I didn't have him on my committee, but as my theoretical framework matured I came back to Gramsci and have him to thank for it. I am grateful for having told him that.

I had the incredible privilege of sparring with Michael over the sociological canon at the Decolonizing Sociology conference that Brown hosted in 2021, and we later published the exchange in Critical Sociology. In a message titled "Thank you," he wrote to me and my co-panelist,

"Thank you for your papers responding to my paper. I enjoyed hearing both of them. It was both an honor and very moving to be taken so seriously.

I like to think it is a tribute to Berkeley's department that a new generation of sociologists should be inclined and feel free to criticize an old generation!"

I thought, but never told Michael, that it was not Berkeley that gave me that space, but him. Michael had a special humility to listen to junior scholars and to take pride in a challenge. There was no fear or awe, only warmth and welcome.

When my book came out, Michael agreed to be a discussant for it and those of several comrades' at ISA Melbourne. Tragically, my mother died just days before our panel, and I canceled my trip. Despite being overwhelmed with sadness and responsibilities, I did not want to miss the experience of Michael - one of my absolute favorite humans - engaging my work. So there I was, up at 4am, Zooming in. We connected later that summer at ASA, and I opened my heart to him about my loss. He listened deeply and shared stories from his own life that were profoundly personal. It was a healing conversation that I still hold onto when I grieve her.

After our ISA panel, Michael wrote to me,

"Yes, Jordanna, I don't think one ever recovers from the death of one's parents, but one just gets used to the idea. But one can continue communing with them, having conversations with them, remembering them. One of the great things in life is memory.

I've no doubt that your own children will console you in these times of grief. Best, Michael."

We are all Michael's children. May we be there for each other now.

Jordanna Matlon

Berkeley Sociology PhD alum

Tribute to Michael B.B. Burawoy

Every time I cross the street, I think of you. For an extraordinary man who traveled the

world over and over, how mundane to leave us two blocks away from your home. Were

you just stepping onto the crosswalk? Were you halfway across Grand Avenue? You did

not use a cell phone, and your eyes were more alert to the world around you than most.

You must have seen that SUV coming, but it was 7 pm. Dressed in your usual black

corduroys—the ones you inevitably covered in chalk every single class—black jacket,

and leather cap, you might have blended into a dark winter night for a drunk or

distracted driver who did not care for crosswalks.

You did not care for cars. All your life you biked to work. You got doored once on

College Avenue on your way to campus. Remember? I was waiting outside your office

when you arrived with a hand wrapped in a mitten of toilet paper. I rushed you to the

hospital. Seated beside you as a nurse stitched your wound 18 times, you turned to me

and said, “so, about those qualifying exams.” Both dedicated and incredibly stubborn,

you insisted on holding office hours in an Emergency Room that afternoon. Even then, I

enjoyed talking to you.

“Interesssssttiiiinnngg,” was one of your favorite words, now echoing in my mind. You

pronounced it slowly, rocking your head, munching on the syllables and the ideas,

affirming, encouraging, even when disagreeing and about to flip an argument on its

head and inside out. I often catch myself doing the same in office hours with my

students. I trace my compulsive nodding and the best of my teaching tricks to your epic

social theory class—I took it once for my doctoral qualifying exams, and a second time

teaching with you, my favorite year at UC Berkeley.

It was during that second year on March 4th, 2011, that you taught Foucault on the

footsteps of Wheeler Hall in solidarity with all protesting fee hikes. I had a good angle to

take a picture that would become your favorite picture of yourself (pic below), now

headlining hit-and-run articles and memorials. “Those were the days!!” you wrote of the

picture years later. You had retired from teaching theory—I never thought you

would—and I invited you to guest lecture in my social theory class. Seated among my

students for a new—and final—lecture on W.E.B. Du Bois’s Black Reconstruction, I

marveled at your ability to translate the most complex arguments into simple

sketches—your trademark, alongside screaming “BB!” for “Bloody Brilliant” students

answering the questions you posed to keep them engaged.

We walked home after class and picked up my three-year-old daughter from her

daycare along the way. You joined my husband, daughter, and I for dinner. You were

family. You gifted my daughter a Paddington Bear, which she loved then. You might not

want to know this, but just recently, I spotted Paddington Bear towering a pile of bunnies

with distressed haircuts and band-aids that my now kindergartener has outgrown and

wants out the door. Two days later, I heard the shattering news and reached out for

Paddington Bear, grateful he was still there. I’m holding on to this one. I’m holding on to

your kindness, your bloody brilliance, and all my memories of you.

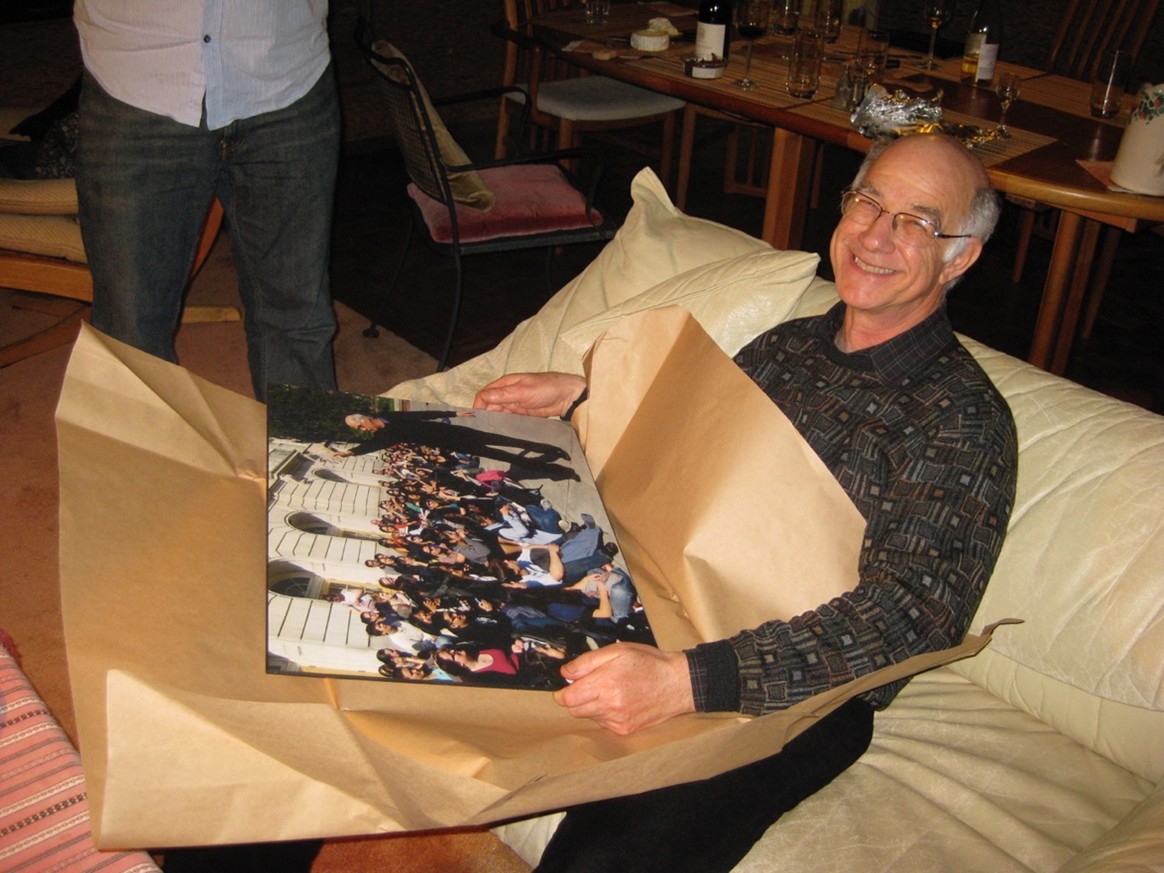

Picture: The six of us teaching theory in 2010-2011, Adam Reich, Elise Herrala, Kate

Maich, Nazanin Shahrokni, Zach Levenson, and I, gifted Michael a framed copy of his

March 4 th picture lecturing outside Wheeler Hall. He loved it, and we loved him.

May he live forever in our hearts.

Ana Villarreal, Berkeley PhD 2016

Tribute to Michael Burawoy

Written by Joanna Reed, on behalf of the UC-AFT Bay Area Chapter executive board

David Skolnick, Timothy Vollmer, Jose Adrian Barragan-Alvarez, David Walter, Balthazar Beckett,

Nicholas Dehler, Sarah Rosenkrantz, Tehmina Khan, Joseph Klett, Anibel Ferus-Comelo, Ramona

Collins, Margi Wald, Jennifer Nelson, Cameron Clark, Catherine Bordel, Khalid Kadir, Barbara Barnes

We, the members of UC-AFT, the union that represents lecturers and librarians across

the UC system, wish to express our profound sadness and grief at Michael Burawoy’s

passing. Michael was an unrepresented member of our union for decades, which

speaks volumes in expressing his support for lecturers’ struggles for living wages, more

secure working conditions and for the recognition of our contributions and membership

in the university community. Michael worked to break down barriers across different

faculty job titles and hierarchies to emphasize our common ground in the face of the

ongoing neoliberalization of higher education. Through his work as Berkeley Faculty

Association Chair, he collaborated with UC-AFT in organizing events and speaker

panels where lecturers and tenured faculty shared the stage, creating rare spaces for

dialogue and collaboration and stirring activism across faculty ranks in support of public

education. He advocated for lecturers in the Academic Senate, co-authoring a study

entitled “Second Class Citizens: A Survey of Berkeley Lecturers” and helped to pass an

Academic Senate resolution in support of lecturers during our last contract campaign.

He was a familiar presence at our protests and rallies, an eloquent voice of support.

I was fortunate to know Michael across two related contexts—I was part of the campus

leadership of UC-AFT when Michael was BFA Chair and his colleague in the Sociology

department.

As a colleague, Michael went out of his way to make lecturers feel like we

were valued members of the community, and that we were in fact experts on teaching

that others could learn from. Despite his stature in the field and his own renown as a

teacher, he would seek out teaching advice from us. He worked to make the department

more welcoming for all faculty, tenured and non-tenured alike. These were countless

small things that added up to a big difference. Reorganizing department mailboxes,

advocating for adding lecturers to listings on the department website, inviting lecturers

to lunch, nominating lecturers for awards, organizing a teaching colloquium for lecturers,

senate faculty and graduate students, attending lecturer bargaining sessions—these are

just a few examples. In his daily interactions he worked to build community and remove

barriers that could stand in the way. He did this with charm and grace and humor. He

also inspired confidence in others and inspired us to do our best work as public

sociologists. I know he did that for me. He would say, “Joanna, you are representing an

organization of more than 1000 people on our campus. You speak.” Or, taking the time

to listen to a radio show where I was a guest and telling me, “you sound as if you have

been doing this all your life”. He found the time and care to make so many of us feel that

we had valuable contributions to make.

A lifelong scholar of labor, he would say that he turned his attention to his own

workplace once he could no longer work in factories. As UC-AFT co-chair, when I tried

to thank Michael for speaking at yet another rally, or helping organize another event, he

always waved me off in his characteristically modest way. He considered it a matter of

course that he would contribute his time and talents to support lecturers, as we were engaged together in the fight for public education and for upholding the teaching

mission of the university. For him, it wasn’t worthy of mentioning, but to the rest of us his

support was deeply meaningful because we knew that his level of advocacy and

commitment was rare, as was his humility, openness and friendship. He would say—if

the university is going to meet its teaching obligations by relying on non-tenured faculty,

then “lecturers should have careers”. I feel deeply grateful that I had the chance to know

and work with Michael and consider him a friend. He was an inspiration to so many of

us. He left us too soon, and with so much important work undone. I hope that we can

honor his legacy by continuing to fight for public education, by enacting the values of

community that Michael held dear, and always, to put our hearts and soul into our

teaching.

Open Letter in Memoriam Michael Burawoy

21 February 2025

It’s hard even to imagine, that Michael Burawoy, my enthusiastic teacher, colleague and friend

for almost three decades pass away. I am writing to say openly about multiple meanings of

works with Michael for me personally and, as I think, for my colleagues-sociologists, with

whom he has studied the “Global North”. But I will only point out three turning moments in my

professional and academic career in which Michael was meaningful to me.

Many years ago, at the beginning of 1990 th , I met him the first time in Vorkuta. It was summer.

And I could take a break from writing my PhD thesis for the degree of Candidate of Sociological

Sciences in Moscow. I happily agreed to accompany a well-known professor of sociology from

Berkeley for a week as a translator and gatekeeper for this short time. For me, he was an

‘American Marxist sociologist’ who came to a polar city, one might say to the ends of the Earth,

to study the rise and the fall of the miners' movement in Soviet Russia during the transition

period. I was astonished how far he could go to develop sociological theory. And we discussed

with him the possibilities of applying Western theories to such ‘latitudes’ and to my research

topic.

Then, till the end of 1990th , we worked together almost every summer in Syktyvkar, in the Komi

Science Centre, where I returned after defending my PhD thesis. I could say that we worked in

the same labour collective. Moreover, we were at roughly the same ‘site’ but with different

research projects. Together with Pavel Krotov and Tanya Lytkina, he was studying two local

factories there. At the same time as I was studying other enterprises in the city, collaborating

with my friends from some Russian regions, conducting numerous studies within the Institute for

Comparative Labour Studies (ISITO) together with Simon Clark. I guess, despite differences our

research teems had some similarities. We discussed our findings, argued, joked and supported

each other to raise the sociological imagination, expand the meanings of the Soviet legacy and

explore strategies for living in a renewing society. Since that time, I have been inspired by his

idea of returning knowledge to where it was received. Together with Tanya Lytkina, and

sometimes individually, we published many papers addressing Russian sociologists and other

social scientists.

At least we met once again in St. Petersburg both working at various universities and facing

dramatic change within neoliberal academia. At that moment he traveled around the world with

his 11 theses on Public sociology. In 2007 I invited him to give a lecture at St Petersburg State

University. But the university managers insisted on a series of lectures during one week. I asked

him if he was ready for such a challenge and he agreed. Despite the tight two-day schedule, he

also agreed to speak at the European University of St. Petersburg and the Centre for Independent

Sociological Research. Moreover, in 2015 he came again to St. Petersburg and once again spoke

at several sociological centers. And yet again I was embraced his openness to different

audiences.

What else’s? The last time I have meet him in Vienna. After one of the working days of the 3d

ISA Forum of Sociology ‘The futures we want: Global Sociology and the Struggle for a Better

Life’, we met in a café, drank coffee, talked about the changes in our lives and even argued about

whether to tip. At every opportunity he was willing to meet with me. Every time he was very

fast with response to me, signing all messages with “Love”. Only my last message to him was

without answer. As always, he left a puzzle, didn't give an open answer, but left the door open to finding another path to solve it. But what is “love”? Is it power or gold, is it work or something

else? What individuals or communities should loss to enhance “common sense” of love? Now I

think, that he knew that love winds the clocks of time and life. Also I think or may be just feel,

that Michael loved Russia. He talked sometimes, that he had broken his mind with research on

Russia. Anyway he planned to be back feeling or knowing that only with Sociology – Public,

Professional, Critical and Policy – together we can understand, discover, resolve and even

reconstitute these puzzle how to make the better world for human beings.

Svetlana Yaroshenko,

Independent researcher since 2022

Summer fields [Sommerfeld], Germany

[Invited guest and participant of the Course by Mary Beth Kelsey with title

“Gender and society: the sociology of women”.

University of California, Berkeley, 2000

Chair of economic sociology department in Komi science center, 1998- 2006

Dear Sociology Folks at UC Berkeley,

I am Dean Stevens, Administrator at The Community Church of Boston. We are a radical congregation of long standing a Sunday morning speaker series.in the City of Boston. We just heard the news about Michael. We send you our deepest condolences.

Michael was scheduled to speak at the church this Sunday. He was going to be here in person, and was going to be with friends in Cambridge. We are shocked.

His friend and colleague in Boston, Miranda Dotson, might join us, to talk about Michael. His address was to be titled “WEB Dubois and the Question of Palestine”, based in large part on the book he wrote about DuBois (who spoke many times from our pulpit from the 30’s to the ‘50s). His last address, in 1959, is digitized on our YouTube Channel.

Dear UC Berkeley Sociology Community,

I am sharing an obit, Michael Burawoy, the People’s Sociologist, which we recently published in Frontline.

Michael’s writings were deeply inspiring and shaped my understanding of sociology and its role beyond academia. I always believed I would meet him someday and thank him for being a guiding light. His sudden passing felt like a personal loss, and I felt compelled to co-write this obituary-- to express my gratitude posthumously in whatever small way I could.

May dear Michael rest in power. Grateful to UC Berkeley Sociology Department for nurturing one of the finest sociologists.

--

Nancy

Department of Sociology

Delhi School of Economics, University of Delhi, 110007

When Someone Sees You

To Michael Burawoy

February 4th, 2025

Sandra Portocarrero

Berkeley Sociology Class of 2012

I woke up to a fragmented, bellicose world that no longer has Michael Burawoy in it. I am trying to comprehend the confusion I feel, the anxiety that woke me up at four in the morning today, thinking of how absurd this world feels. I decided to do what he taught me best: to reflect. Michael, here is my reflexivity exercise: how I see myself through you and how I see you.

2010. I was a community college transfer student majoring in sociology at Berkeley. I did not know who Michael Burawoywas, but whoever manages the lottery of life decided that the insecure, passionate about justice, opinionated, and emotional 20-something-year-old Sandra would have Michael teach her sociological theory. It was a two-semester class, so in addition to another course I took with Michael, I saw him in the classroom for 1.5 years. Everyone who knew him knows Michael gave his best to others in the field, the classroom, and his friendships. He was crazy beautiful. He loved the word hegemony, Frantz Fanon, and teaching about the struggles of the working class to his students. He loved talking about the capitalists, who were digging their own graves! But the 14 years of friendship with Michael started during those intimate spaces of growth called office hours.