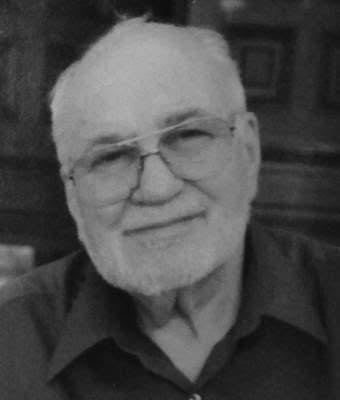

IN MEMORIAM: BOB BLAUNER PASSED AWAY ON OCTOBER 20, 2016

I have received sad news: the passing of Robert Blauner at the age of 87. Bob – as he always insisted on being called – was a Berkeley graduate student in the 1950s, receiving his PhD in 1962. He became a faculty member in our department in 1964.He had a distinguished career.

He was the author of such classic studies as Alienation and Freedom (1964), partly informed by his own experiences as a worker for 5 years at International Harvester in Emeryville – a book that prefigured the subsequent rise of Marxist studies of the labor process; Racial Oppression in America (1972) that deepened and popularized the idea of internal colonialism – a critical contribution to the transformation of race studies in the 1970s – that was updated and expanded in 2001anticipating the discussion that has erupted nationally today; Black Lives, White Lives (1989) which portrayed race relations through and after the civil rights era based on extended interviews with blacks and whites between 1968 and 1986; Our Mothers’ Spirits (1997), a compassionate collection of men’s writings grieving the loss of their mothers; Resisting McCarthyism (2009) which focused on the brave Berkeley faculty who refused to sign the Loyalty Oath, and on the politics that set the stage for the Free Speech Movement.

Bob was a man of integrity and principle in practice as well as in theory. His promotion to Full Professor was long delayed because of his outspoken criticism of the McCone Commission that investigated the Watts rebellion of 1965. Bob had been a member of the Commission’s research team, but then resigned in opposition to its law and order approach, prompting him to write his (in)famous article, “Whitewash over Watts”. In 1978 he incurred the wrath of his colleagues when he accused one of them of sexual harassment – a term that barely existed at the time. The case became one of the early milestones in the movement against sexual violence. He was ahead of his times in other ways too. With Troy Duster he began Affirmative Action in the Department, actively recruiting students from the South. And for 20 years, starting in 1975, he taught a course on men’s lives, trying to grasp the other side of the gender revolution.

Bob retired in 1993 to spend the next 23 years doing what he always enjoyed, following baseball, playing chess and poker, above all writing his memoirs, and living a life devoted to his wife, the filmmaker, Karina Epperlein. He died of a kidney disease which had afflicted him for several years.

Michael Burawoy.

From Yiannis Gabriel. Bob was a man of great integrity, compassion and intelligence. I attended two of his graduate classes and he was one of the members of my dissertation committee. More importantly, he sponsored several courses organized and taught at Berkeley by graduate students like myself, putting his signature on various documents to satisfy University of California bureaucracy. Bob also put his signature on numerous 'nearly' truthful statements that kept me out of the Greek army at the time.

Bob's academic work concentrated on the sociology of work, race relations and what was at the time an embryonic field of death studies. His Alienation and Freedom (1960) tried to initiate a new life for the concept of alienation, a hugely popular and much abused term in the sixties. His attempt to link alienation to different levels of automation was generally criticized by Marxists for psychologizing alienation and by industrial sociologists for being technologically determinist. Yet, when Braverman did something similar ten years later using the concept of deskilling, it proved to be a major breakthrough in neo-Marxist studies of the labour process.

In race relations, Bob theorized the concept of internal colonialism, long before postcolonial studies had emerged as a discipline. Again he antagonised Marxists who had, until the 1970s, tended to see racism through the prism of 'dividing the working class'. Yet, I can think of no greater advocate of race equality and equal opportunities in the US than Blauner, as evidenced by his stinging critique of official report on the 1965 Los Angeles riots in "Whitewash over Watts".

I last saw Bob in the summer of 2009. As ever, he was full of life and ideas. What I will always remember about Bob is that he embodied the ideal of a scholar who scorned to differentiate between the personal and political long before it became a cliche. He not only brought his politics into every aspect of his life but he refused to shelter his personal life from the wider political arenas, making himself vulnerable and being unwilling to cover up contradictions and dilemmas. In particular, he refused to shelter himself from Berkeley graduate students who, at least in the 70s, did not have a great deal of respect for the intellectual and political qualities of the faculty.

From Larry Rosenthal. I came late to knowing Bob. There were some meals together. With Karina. Always lovely. Bob, his characteristic—or so it seemed to me—fluctuation between taciturn and suddenly funny. He sent me some autobiographical writings. They were profound and moving. I answered him at some length. There was now a bond between us. We saw something of ourselves in one another.

I got invited to his poker game. It was a table full of basically sweet and aging men. But, as poker will have it, an individual trait became exaggerated. Became one’s poker persona. Bob’s persona? While the poker players have long been on to this, it might come as a surprise those who were not at the table. Bob was the banker. Always the banker. He insisted on it. He brought the chips. He counted them out. Collected our greenbacks. An accountant’s seriousness about it--even though we were still playing in 2015 for stakes that were low, low end already in 1975. You get cleaned out? Bob will sell you more chips. At the end, cashing in the chips, meticulous, almost fussy, about the final quarters coming true. Was this a pole away from the labor organizer and the theorist of alienation? Somehow it never seemed that way.

From Leon Wofsy. I had great respect for Bob. We became close during the time of the Free Speech Movement, the movements against the Vietnam War and, later, against South African Apartheid. Actually, when I came to Berkeley in 1964 and met Bob, he reminded me that we had come together in the Labor Youth League in the 1950s. Bob was so different from most academics, so rich in insights and human connection with the “common folk.” He was so genuine, so original and unpretentious. However his views developed and changed over the years, he was always unwavering in integrity and principles.

From Colin Samson. Bob was one of my teachers. He made a deep impression on how I think about the world and about myself. He taught me about oral history; its techniques and its importance as a vehicle for affirmation of people who are so often ignored and dismissed. His classes were open, convivial and he was always generous to everyone. Bob built a community out of our class, enabling us to learn from each other, from him and from the many sources he opened up to us. The lives of people were always personal and political, and as students he helped us see that scholarship was political. How could it be anything else? I will always remember Bob as a person who made me think "I want to be like you". If I have inside me only a small amount of what he showed, I will have succeeded at something. Rest in Peace.

From Richard Apostle. My sincere condolences. Bob could spot a plebe in need at great distance, and very kindly invited me over for occasional chess games during bad patches. Along with another faculty member, he was very much responsible for my navigating a system which remained a puzzle to me for decades. Also, I very much appreciate the opportunity to come and visit you both a few years back. It meant a lot to be in your graceful presence.

From Robert Kapsis. It was the early 1970s during a session of his graduate seminar on race when Bob eloquently defended me against the wrath of Black Nationalist graduate students who were horrified that a white liberal graduate student (born and raised on Chicago’s North Side) would have the audacity to pitch the idea of doing a dissertation about the black community of Richmond California. Thanks in no small measure to Bob’s encouragement, I wrote the dissertation and published a series of scholarly articles based on the research. My interest and curiosity about the black experience continues to this day. In 2011 I published a book length study on legendary African-American film director Charles Burnett (1944- ) to coincide with the opening at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) of the first complete retrospective of Burnett’s work, which I conceived and co-organized. Thanks Bob.

From Michael Lerner. Bob Blauner was an amazingly wonderful human being, as you know Karina. He wrote for Tikkun and my friendship with him goes back to the 60s when he was one of the most reliable faculty people we students could count on when the administration would attempt to squelch our activism. I felt he never got the recognition he deserved, particularly for his work against racism

From Rivka Polatnick. As a sociology graduate student in the '70s and early '80's, I had the pleasure to take courses with Bob and was delighted by his combination of scholarly excellence, political and moral commitments, engaging teaching style, and humanism and kindness. When it came time to choose a dissertation chair for my study of late '60s Black and White Women's Liberation pioneers, my mentor Arlie Hochschild was on leave and not taking on any new dissertations. I was very happy to have the fine alternative of asking Bob to be my chair, and he responded with enthusiasm. He guided me through the process with skill and warmth, and I am indebted to him. He was very helpful in writing me letters of recommendation, and my own teaching incorporated his scholarly work and pedagogical style. I will remember him with great respect and fondness.

From Nicole Biggert. I was a graduate student who knew Bob in the late 1970’s and until I graduated in 1981. Bob did not like the formality of a classroom but when it came time to talk about ideas that he cared about the passion came through and there was no better teacher. One issue that really hurt him deeply was the criticism he faced as a white man who had dared to write about race in America. He was caught in a political conundrum and allowed us to talk about this personally painful issue as a way to help us to learn and to sharpen our understanding as sociologists. I always appreciated his generosity of spirit.

From Charles Garvin. Bob and I first became friends when I moved into his apartment building when we were ten years old. I was one month younger than him. I remember many things -enough to write a book. Bob was on the Quiz kid program on radio once and I remember him saying in response to a discussion of money that it can't buy love. He was an avid sports fan and played tennis I think. He was editor of our high school paper and also class validictorian. He immediately went to University of Chicago after high school where I joined him two years later. We became roommates a year later along with others who each became famous in their own ways; Aaron Asher on book editing, Leo treitler in music and Dan Joseph in engineering and physics, and I may add myself in social work. Bob and Dan married early and the two couples went to France to live for awhile to escape the McCarthy period. When they returned and as part of their political commitmernt they went to work in factories for awhile which fed into Bob's studies of worker alienation when he left factory work and reentered academe. We have been in touch ever after: first, when he was a sociology student at Chicago and later, when he went to Berkeley although others can say more about those years.

From Susan Takata. I was so saddened by the passing of Bob Blauner. I was at Cal between 1975 and finally obtaining my PhD in sociology in 1983. I took several of his grad courses including the early beginnings of a gender course that you mentioned below. To date, when I teach “Race, Crime, Law,” I mention Bob’s book, Racial Oppression in America. When I first met Bob, he had this gruff exterior but as I got to know him, he was actually a very nice guy, and a very caring teacher. After receiving my Ph.D., I got hired here at UW Parkside in sociology in 1984, and in 1997, I became the founding mother of the Department of Criminal Justice, one of the largest majors on campus. I kept in touch with Bob. We exchanged Christmas cards each year. I will miss Bob. He truly cared about his students.

From Lois Benjamin. For forty-nine years, I have known Bob as my professor, advisor, colleague, and friend. In September 1967, I first met Bob when I enrolled in his Race Relations class. As one of the first two African American women to be admitted to the graduate program in the Department of Sociology (1967), I was immediately drawn to his integrity and sensitivity to others, his openness to myriads of ways of knowing and understanding, and to his critical, pedagogic approach on racial/cultural politics and power. His lectures and the attendant discourses were animated and civil. A brilliant scholar, Bob was at the leading edge of academics who challenged the conventional analysis and wisdom of race relations in United States in the late sixties. His fresh, penetrating writings and lectures were influential in shifting the focus in race relations from prejudice and discrimination to institutional racism. Additionally, he was instrumental in deepening the analysis of the construct of internal colonialism. In his Race Relations class, I wrote a research paper on the impact of racism on black male/female relations. Bob encouraged me to use the work as a basis for my dissertation. At that point, he became my academic advisor and mentor. Later, he chaired my dissertation committee. Bob always wrote in a clear, elegant style and he encouraged his students to write likewise and to shun turgid academic prose. He would say, “My goal is not to turn out another Talcott Parsons.”

After receiving my doctorate, Bob and I remained in contact throughout the years. As colleagues and friends, we shared, critiqued and supported one another’s articles and works in progress, as well as championed each other during promises and perils of our professional and personal lives. I have been fortunate to have many magnificent educators who have impacted my life; however, as I stated upon Bob’s retirement in 1993, he, along with my third-grade teacher, had the most profound influence in my educational journey and life path.

From Michael Kimmel. When I arrived at Berkeley in 1974, Bob Blauner had already influenced me twice. I'd read Alienation and Freedom (a book title that I'm sure most of us wish we'd thought of!) as an undergrad and was moved by the way Bob described these workers' lives with such empathy. But the article, "Internal Colonialism and Ghetto Revolt" blew my mind when I read it in my first year at another grad school. Here was the analysis that I thought I was looking for - that applied the analysis of our imperialist adventures in Vietnam to the maintenance of an internal colony here at home. When I finally met him, I was struck by the combination of his humility and his enthusiasm. He listened to people, cared about them, and was astonishingly self-effacing about his own stature in the field. My research took me towards others in the department (and in the history department), and my dissertation about 17th century French tax policy had less than nothing to do with Bob's move towards gender and masculinity studies. His interest was only secondarily academic, spurred by years of analysis and serious soul searching. And the way that Bob fused the personal and the analytic in both his teaching and his research was the third, and most significant way, he influenced me. He became a friend and a mentor, especially after I had begun my career. Who else would call himself a proud Mama's Boy? Mike Messner and I dedicated the most recent edition of Men's Lives to Bob. I'll miss him.

From Paul Joseph. Bob played a major part of my graduate studies at Berkeley. This was in the early 1970s, his book Racial Oppression in America had just come out, and the department was continually caught up in many of the national and Bay Area developments occurring at the time. Bob’s work, particularly his discussion of internal colonialism, played a central role in these discussions. I know that many of my peers were influenced by his views, and inspired by his presentation of what sociology could be.

We became and remained friends. He played softball in the Friday afternoon game behind Barrow Hall. We played tennis together and I joined him and other faculty in a monthly poker game. Bob was very personable and approachable; he served as a most valuable mentor to a young person navigating the entry points of the sociological profession. We had a meal together whenever I visited and I followed the progression of his interests through his other books on race, masculinity, and eventually the loyalty oath. I especially remember his voice: strong, resonant, and populist. When Bob spoke, democracy seemed to carry in its timbre.

From Mike Messner. It saddens me to hear of Bob’s death, and I want to share a couple of thoughts. Though I'd already known him by reputation for several years, I first met Bob at the department orientation for new grad students in the Fall of 1979. Several professors and continuing grad students addressed our incoming cohort. Most speakers spun self-congratulatory platitudes about the greatness of the Berkeley sociology department, so it really impressed me that when Bob spoke, he encouraged us to try to construct balanced lives while in grad school by exploring the beautiful Bay Area and spending time in the lovely parks in the area. I realized immediately that this was my kind of person: I wanted to work with Bob Blauner. And I wasn't disappointed. Bob was a helpful mentor with my work, and I learned a lot by working as his assistant for three years in his large undergraduate course on men’s lives. Some say that this was the first such course taught in the nation. Whether it was or not, it was hugely successful. Quite simply, Bob was the best large-group discussion facilitator I have ever seen. The discussions in his class were remarkable because Bob set the tone and created a safe space for expressions of painful personal experiences such as rape, or coming out; or he created an illuminating framework for discussions of seemingly mundane topics like men’s friendships. As a facilitator, Bob had the ability to interweave various strands of a group discussion and then present it back to the group in the form of an analytical question. After working to emulate this style of teaching, with some limited success, I now conclude that Bob had a true gift for this sort of teaching. His many students and TAs were blessed by his sharing of this gift.

I was happy to re-connect with Bob a few years ago. We were both writing memoirs and it was a joy to share our works in progress with each other. When Bob’s Resisting McCarthyism was published in 2009, I was organizing the Pacific Sociological Association meetings in Oakland, and I was very proud to organize an author-meets-critics session that drew a nice group of admirers.

From Juan Oliverez. I was one of those minorities to benefit from Affirmative Action. I was admitted in 1971 and earned my PhD in 1991. From 1988 to 1991 he formed a group of students to assist them with the completion of their PhD. I was one of them. I am very sad to learn of his passing. He was a great friend to Chicanos and all students. I was honored to know him personally and professionally. He cared about me as a person and as a student. I have to say that he was my favorite professor. May he Rest in Peace. He will surely missed and appreciated by his students.

From Magali Sarfatti Larson. I am deeply saddened by these news. I can see Bob Blauner’s face in front of my eyes, hear his comments about jury selection, remember the conversations in his office, the discussions about Alienation and Freedom and especially about the United States and the Sixties. Bob was in so many ways the symbol of what we believed. I could not take a course with him during my time at Berkeley, because he did not give graduate seminars during that time, but I asked him to be on my dissertation committee, even though I was not doing research on something of direct interest to him. But then, everything was of interest to him and, for me, having a reason to talk with him was a privilege. He dignified our discipline and our calling. His life was a paragon of intellectual and political integrity. We will not forget him.

From Douglas Davidson. I have fond memories of Bob. He along with Troy Duster, and a collective of fellow Third World Liberation Front supporters in the graduate student population were vital to my ability to navigate the often tumultuous waters of doctoral studies at Berkeley. He influenced my life and work in more ways than I can illuminate in this message. His contributions were immense and he will be sorely missed. Please pass my condolences to his family and close departmental associates and colleagues. peace--douglas Davidson: former student and mentee

From Teresa Arendell. Thank you for the notification of Bob's death. I entered the UCB graduate program in 1979. Bob seemed to recognize that I had a passion for learning but no cultural capital, coming from an impoverished level of the working class (and being a mother of a young child). I finished the PhD program in large measure because of the support, intellectual challenges, and kindnesses of Herb Blumer, Arlie Hochschild, and Bob Blauner. Bob's analyses of class and racial, and later of gender, stratification and oppression were formative in my becoming a sociologist.

From Eloise Dunlap. I am very saddened to hear of the passing of Dr. Robert Blauner. He was my life vest while studying at Berkeley. I do not have the words to express what he meant to me. It is due to him that I am able to enjoy a 30 year career as a research scientist writing NIH grants and acquiring funding. Dr Blauner truly cared for his students and spent time helping us to understand concepts. There was no limit to his efforts to be of help to his students. I will always remember him with love and fond memories.

From Faruk Birtek. It is very sad to hear of the passing of Bob Blauner. More than fifty years ago he was gracious to let me - as an undergraduate - into his graduate seminar. He was a most enthusiastic, bright lecturer, and at the end of the term he spent much time discussing my paper. We later became friends, although only running into each other infrequently due to geographical distances. His book, Alienation and Freedom, was a break-through at the time, in the midst of a lot of talk about alienation with no substance other than Marx's. He was a person with great politics, very big heart and brilliant head. I am sad, Berkeley will miss him. I especially miss him as I write from the other side of the globe with a lot of hell around.

From David Nasatir. Bob was a good friend for a long time. One bit of of arcana that may have been overlooked is Bob's identity as a "Quiz Kid". You may not recall this radio program from the 1940's, but Bob was a "contestant" on the show of October 8, 1941 along with Gerard Darrow, Ruth FIsher, Emily Israel and Van Dyke Tiers. Always a smart guy!

From Jeffrey Prager. I'm sad to hear the news about Bob. I was his student between 1969-1977 when he was deeply involved with research that culminated in Racial Oppression in America. I was in sporadic contact with him after that, usually when, early on, he came to visit his mother in Los Angeles and, later, at UCLA when he was speaking on various of his new projects. I remember his taking great interest in my psychoanalytic training while he was working on his book of essays on mothers. He had a very close relationship to his mother. He would come often to visit Los Angeles, where she lived, and grieved greatly when she died. The last time I spent extended time with him was when he visited archives held at the UCLA library. He was in the midst of his research on McCarthyism in the University of California.

Early on in my graduate career I became one of his research assistants, "coding" the in-depth interviews he had collected on racial attitudes and experiences by both white and black respondents. I was the junior member of the team, joining the project after all of the interviews were completed. But I was quickly introduced to a research team that straddled the academic and political world, and that brought into Berkeley sociology many people at least as strongly committed to political activism and social change as they were to academic sociology . Hardy Frye and David Wellman were the seasoned veterans on the project, having already developed close relationships with Bob. I felt extremely fortunate to be able to become a part of this team.

Bob was a very funny guy though not usually a happy one. He always straddled at least two worlds at once, always with a pretty light touch. He ever remained the working class labor organizer who, a bit uncomfortably one imagines, found himself in the academic setting. His early interest in alienation, I think, was no accident. Whatever world he was in, he never felt entirely a part of it and estrangement from the norm was his way of being in the world. This may have improved after his retirement but I do remember his infatuation for a time with primal scream therapy. He always needed to be elsewhere at the same time. When he arrived for my oral exams in 1974, he walked in with a radio with its electric cord wrapped around it. He asked if it would be possible for us to listen to the Watergate hearings during the exam. The more staid members of the committee prevailed!

Throughout his career at Berkeley,Bob prided himself on being down-to-earth. He exemplified the politically engaged sociologist whose audience extended beyond the academy. This was a point of pride for him. Racial Oppression in America was masterful for its clear, direct writing and its bold explication of a controversial thesis. Both his writings and his being were incitements to make personal and political contact with others--inside and outside the academy--and to never allow academic scholarship to lose its fundamentally moral bearing. He has remained an inspiration for me. My first publication appeared in The Berkeley Journal of Sociology in 1973 on "White Skin Privilege". Now, some 43 years later, I just completed an article for publication entitled "Do Black Lives Matter? American Resistance to Reparative Justice and its Fateful Consequences".

Bob of course will be missed but, for me and scores of others, he made a lasting impression.

From Marcel Paret: I met Bob Blauner in 2006 during the planning for the annual BJS conference. It was the 50th anniversary of BJS, and the theme for the conference was Power. Alongside Troy Duster and David Wellman, Bob was part of a panel on the topic of "Power and Insurgency: Communist and Anti-Racist Struggles in the University of California." He presented on the work that would eventually become Resisting McCarthyism. In one of our email exchanges devoted to planning the panel, he promised to "tell amusing stories" about David Barrows, of Barrows Hall, among others. I think he did, in the end. But I was a bit star struck. I had come across Bob's work on internal colonialism in my reading around issues of race and class, and thought that he was onto something important. In my letter inviting Bob to present, I expressed appreciation for his involvement in social justice movements, his critical research on race and work, and how he had shaped Berkeley sociology. Bob reminded me that his first article was published in BJS, in 1958, and noted his surprise that I was familiar with his work. He thought that Berkeley sociology had moved on to a different kind of sociology. I don't know if he was right about that or not (in my case he was certainly wrong). But it reflected a deeper humbleness that was evident to me when we finally met in person. Bob was kind and generous, and I feel lucky to have met him.

From Guether Roth: Thanks for your moving obituary of Bob Blauner. In the fifties we were good friends in Graduate School. As he has written in his autobiography, we were part of a close group, having fierce chess battles at the old Institute of Industrial Relations—he mentions Amitai Etzioni, Pat McGillivray, Fred Goldner, myself--, where we worked under Bendix, Lipset and others. We often played chess on the lawn around the Institute, and I remember his resolute moves on the board. But Bob also mentions the “unbelievable comradeship and solidarity” of our group. We prepared together for the five days of written qualifying exams. The faculty did not like this, but could not do anything about it. Working together through the 75 required books, assembled unsystematically by the faculty, broadened our knowledge beyond our own burgeoning interests. Even more importantly, we learned how to do research from looking over the shoulders of our mentors in the Institute. It was a lucky constellation for becoming a sociologist in an era of great expectations.

From Mary Anna C. Colwell. Thanks for sending the news about Bob. I was an average, underprepared grad student in the very divided department in the late 1970s and was truly an outsider among the very bright graduates from Harvard, Yale, etc. who took Marxist analysis as gospel. I struggled through, put together a dissertation committee (Private Foundations and Public Policy) because of personal connections, and Bob was chair of my orals committee. Afterwards he hosted a small party to celebrate and that may have been the first time I felt like I belonged. He was genuinely kind and I greatly appreciated that.

From Peter Evans. Bob Blauner’s publications and political commitment made him a titan of progressive sociology, but he should also be remembered as one of the most endearing sociologists to inhabit Barrows Hall. He would not, of course, have liked the term “endearing” — too sentimental. Nonetheless, he was thoroughly likable despite being unwilling to back down from what he believed in and quite an unusual person in a business where big egos so often get in the way of thinking and institution building. He knew the value of his work and enjoyed doing it, but self-aggrandizement was never his game.

I didn’t know Bob well but he was still an important part of sociology at Berkeley for me. His retirement party — complete with a string quartet — was one of the most memorable occasions of my early years at Berkeley — an affair full of good feeling but also laced by some speakers with hard edged reminiscences of the political conflicts of earlier decades. I also remember his 70th birthday, held in Tilden Park, where Bob and his friends got sore muscles and various aches and pains by playing baseball, while I, having never had any aptitude, was safe on the sidelines. But, most of all, I will remember his sharp and impish sense of humor often poised to strike as you passed him in the hall of the 4th floor of Barrows. It is always reassuring to see sociology married to sympathetic human sensibility and, in the time we shared in Barrows Hall, Bob exemplified that for me.

From Dana Takagi. Michael, as you no doubt know, Bob was one of the reasons I decided on graduate studies. I strayed from my math major to take a class from him, American Society. Herb Holman, then graduate student but since passed away, was my TA. Bob, always a little quirky spent the first lecture teaching us different ways of reading the NYT. In that big Dwinelle lecture hall, he held forth. He'd brought the paper to class, started on the front page, and discussed the pros and cons of reading all of the front page, explaining the difference between stories above and below the fold, versus reading one story, say the lead on the front page and turning directly to page 14-16 to finish that story. I immediately decided Bob was a nut, enrolled in the class, and vowed to read the NYT every day (which I still do).

When I went to visit him as a senior (still a math major), I was nervous about asking him to write a letter of rec on my behalf for the Berkeley grad program. He scowled. And, he grimaced. In his inimitable way, for a grouch, he said, "no no no, you don't want to do this. Look at me, I'm not so happy about it all.....". He went on for some time during which I redoubled my resolve about graduate work. While I did not work with him during graduate school (he was on to other pursuits even though he was still a professor), I have very fond memories of him. I always thought of him and Matza as two unique intellects, of a certain generation of left thinkers.

I was very pleased to read that he called out the title ix complaint. He was fearless in that way. I recall that period clearly.... I took a class from the harasser in question and recalled much talk about it among my peers. As you probably know, among those peers - who formed WOASH (Women Organized Against Sexual Harassment) - are women now at the top of the field, and they still sometimes gather at the ASA to discuss not the old case but the more general problem of discrimination against women, in all forms, in the discipline.

From Deborah Gerson. Bob Blauner was my committee chair when I filed my dissertation in 1996. As a graduate student and a single mother, I was frantic to finish, which Bob enabled me to do with little drama. It's post Berkeley that I got to truly value his work. As a part-time faculty member at SF State I read and taught Black Lives, White Lives and was moved by the depth and humanism in his interviews. Bob understood, and wrote and theorized intersectionality, before it was a code word. He had a sweetness and kindness that is rare in academia. May his work and his memory serve as models for future sociologists.

From Raka Ray. I met Bob right after he retired. He lived and worked in difficult times for the department, and was pretty alienated when I met him. Yet I hope we never forget what he stood for: That he stood up and called out sexual harassment when few did (in 1978) and that he thought about US race relations in terms of internal colonialism shows the extent to which Bob stood for integrity, imagination and intellect. I am proud to be in a department that he worked in and shaped so many generations of students.

From Paul Rabinow. In a low stakes monetary game of poker among aging lefties of various stripes, the highlight was always the epic confrontations between Bob and his old and dear friend, Hardy Frye! Like a veteran pitcher, Hardy would take his time, delay, feint and fake, re-look at his cards--while Bob fumed. The friendship was palpable.

AUTOBIOGRAPHY

I returned to graduate sociology at Berkeley after five years working in factories where I had been a total failure at revolutionizing the working class. I say return because I spent one semester in 1951 in the department. Then I had absolutely no interest in sociology, because as a communist (Stalinist variety) I had all the answers already and I was in school only for a deferment to keep me out of the Korean War. Reinhard Bendix was not at all impressed with my term paper arguing that Soviet workers were not alienated because they owned the means of production. So that in early 1956 I was afraid that C grade would prevent my getting back into the department. I asked my friend Tom Shibutani if he could help, and maybe he did.

Shibutani had been my main M.A. advisor at Chicago for a 1950 thesis on the social psychology of personal names. But because of my years as a worker and a communist I was now more interested in industrial and social psychology. It was almost as if the new chair, Herbert Blumer, had built a department tailor-made to my needs, which was to make sense of my experiences, and to answer questions about the politics of the working class (Selig Perlman), the similarities and differences between socialism, communism, and capitalism (Schumpeter), why revolutionary parties and movements ossify (Michels), and the appeal, for someone like myself, of ideologies and utopias (Mannheim). Not only did I have great teachers like Kornhauser, Lipset, Selmick, and Bendix (whom I never dared ask if he remembered me), but we had a fantastic cohort, as other bio writers have attested to. My best pal was the late Bob Alford, who had worked at International Harvester with me: other recent local proletarians included machinist Lloyd Street and railroad switchman John Spier, and from Detroit's auto plants, Bill Friedland. At the Institute for Industrial Relations, where I TA?d for Marty Lipset, we had a chess rivalry that included fellow grad students Amitai Etzioni, Guenther Roth, Pat McGillivray.--perhaps the most erudite and knowledgeable of all of us -- and Fred Goldner; a few years later my friends in grad school became Bill and Dorothy Smith. (Dorothy's bio is available, but not Bill's, who after a series of teaching jobs, including one at the University of Pittsburgh, gave it all up to become a plumber before dying from cancer in 1986.)

The comradeship and solidarity in graduate school was unbelievable---I've not yet mentioned Harry Nishio, Ernest Landauer, Art Stinchcombe, Gayle Ness, Walt Phillips, my good friend Ken Walker, and dozens of others I learned from-- in fact it was so good that I wasn't prepared for what I would meet when I began teaching. First at S. F. State, then at Chicago, finally at UCB, my fellow assistant professors were almost the opposite of my grad school peers: closed off, ultra-competitive, or perhaps just afraid that you'd steal their ideas.

My dissertation on factory workers was informed by my industrial experiences, but didn't draw directly on them. But Alienation and Freedom made my career. It got me a job at Chicago which permitted me to be hired back at UCB---the first Ph.D. to return since Ken Bock. It also got me tenure at Berkeley. I am indebted to Selznick, who made me rewrite a draft on the sociology of industries into a more theoretical version.

During the year that I did my M.A. at Chicago Blumer had been like a father figure for me. Though mostly from a distance as I sat in his seminars and marveled at everything about the man. That 15 years later the secretaries at Berkeley would be mixing up our mail is something I never would have dreamed of. It was great to see the Blumer renaissance in the 1960s, for after a period when he had been marginalized, the New Left grad students took to his theories and he gained a new following. But it was too late for Shibutani, who like Blumer himself, was not really respected by the very political and industrial sociologists who were my mentors, and who had been -- most unfairly in my view -- denied tenure.

Sometimes I've regretted that I only stayed one year at S.F. State, because I loved San Francisco, and also, in large part because of pressure from my second wife who hated Chicago, I left my alma mater after only one year. Another regret is that I flitted around in terms of research and writing, from workers to the sociology of death to Black-white relations. Each time I changed fields I had to learn a whole new literature. I would have had a less "disorderly career" (Wilensky) had I just stayed in the area of work, and then as I got inspired by the civil rights movement, studied race relations in the context of the factory.

Had I stayed in Chicago, where the department and the city was much more conservative than Berkeley, it's quite likely that neither my sociological writing nor my personal politics, would have become as radical as they did in the late 60s. I would probably have stayed in Freudian psychoanalysis rather than going through those four years of primal therapy in the '70s, an experience that was life transforming. It led to four years of no writing or research, followed by the decision to work on experiential projects (like Black Lives, White Lives) rather than theoretical ones. And it was the motivation for a change in my teaching style from the lecture format to discussion and an emphasis on personal experience. I am proud of the fact that I was one of the first to offer a course on men's lives, which I taught from 1975 through 1995.

Retiring in 1993 was my best career move ever. Even though teaching got easier over the years, it was never natural for me in the way writing is. As a retiree at UCB you get a cheap parking permit and all the time you want to write. Like Bennett Berger, my writing is 90% non-sociological these days and 90% unpublished. Exceptions are a collection of essays on race (Still the Big News, Temple 2002) and an anthology of men 's writing on the death and lives of mother (Our Mothers' Spirits, Harper Perennial, 1995). I'm quite excited about my current project, a memoir of growing up in Chicago in the 1930s and 40s that is part social history, part family history and coming of age story, with a lot of baseball (the Chicago Cubs) thrown in.